When you use the internet, you almost never think about IP addresses like 192.0.2.1. You type example.com, click a link, or tap an app icon. Human-readable names act as a bridge between people and machines.

In Web3, that bridge is broken again. Most blockchains still show you long, scary addresses like 0x71C7…, which are safe for machines but terrible for humans. The NEAR Protocol takes a different path: it makes human-readable names a built-in feature of the chain, and then connects those names back to the traditional web. This article explains how that works, using the idea of the NEAR Domain System (NDS).

NDS Dashboard (for domain owners)

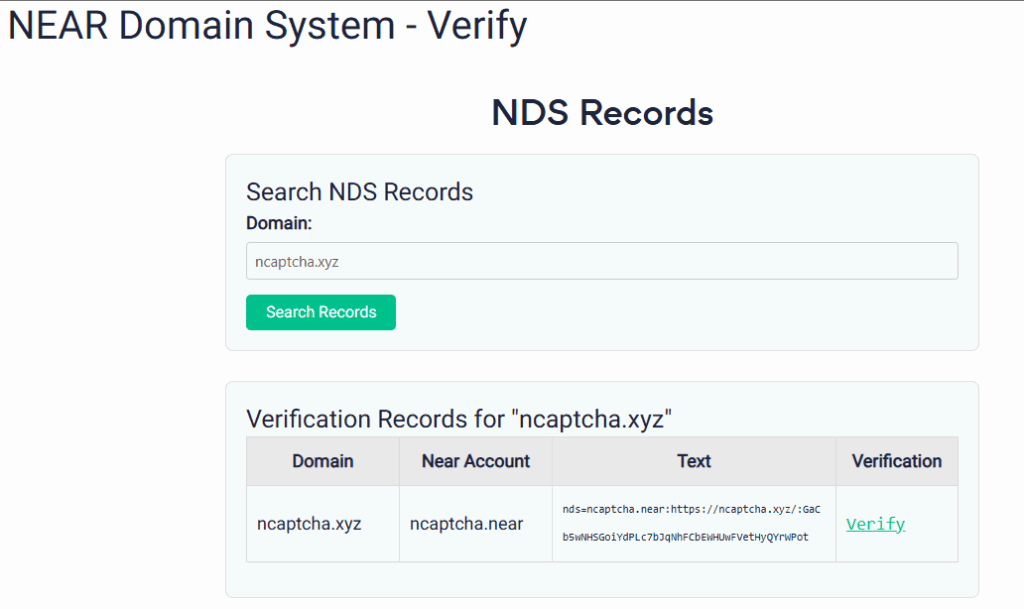

NDS Verifier (for users)

Why Names Matter on the Internet

At first, the internet ran on IP addresses only. These are numbers that computers use to find each other. They are great for routing, but useless for memory and meaning.

The Domain Name System (DNS) fixed this by mapping names like google.com to IP addresses. DNS is organised like a tree:

-

At the top is the root (managed by ICANN).

-

Below that are top-level domains (TLDs) like

.com,.org,.io. -

Below TLDs are second-level domains like

example.com.

DNS stores its data in zone files, which contain resource records. One special type is the TXT record, which can hold arbitrary text. Over time, TXT records became the standard way to prove domain ownership.

For example, when Google Workspace wants to check that you really own example.com, it asks you to place a specific token into a TXT record. Only someone with access to the domain settings can do this, so the presence of that token proves control.

ENS: Names as an Overlay on Ethereum

In Web3, Ethereum popularised human-readable names with the Ethereum Name Service (ENS). ENS uses smart contracts to map names like alice.eth to Ethereum addresses.

Its architecture has two key parts:

-

A Registry contract that knows who owns each name and which Resolver to ask.

-

A Resolver contract that stores the actual data (for example, the Ethereum address).

To send funds to alice.eth, a wallet must:

-

Ask the Registry: “Which resolver handles

alice.eth?” -

Ask that Resolver: “What address does

alice.ethpoint to?” -

Send funds to that address.

ENS can also connect DNS names. With DNSSEC enabled, a user can prove that example.com belongs to a certain Ethereum address by adding a TXT record and submitting a cryptographic proof on-chain. This is powerful, but verifying these proofs directly on Ethereum can be complicated..

The key point: in ENS, the name is an overlay. It sits on top of the underlying account, which is still a long hex address.

NEAR’s Different Approach: Name = Account

NEAR flips this model. On NEAR, the human-readable name is the account.

A NEAR account:

-

Has a human-readable ID, like

alice.nearorcompany.com. -

Stores a set of access keys (public keys) that control it.

This design is called native account abstraction:

-

You can rotate or add keys without changing the name.

-

You can have full-access keys (like admins) and function-call keys (limited permissions).

-

There is no extra resolution step. The name itself is the primary identifier in the protocol.

NEAR also enforces a hierarchical account model, similar to DNS:

-

Only the owner of

nearcan createalice.near. -

Only the owner of

alice.nearcan createapp.alice.near, and so on.

This makes it easy to manage namespaces, such as university.near, student1.university.near, registrar.university.near, etc.

Because each account uses blockchain storage, NEAR uses storage staking. An account must hold a minimum balance of NEAR to pay for the bytes it occupies. This discourages spammy name squatting.

What Is the NEAR Domain System (NDS)?

In this context, the NEAR Domain System (NDS) is a service and a set of standards that:

-

Link www domains (like

ncaptcha.xyz) to NEAR accounts (likencaptcha.near), and -

Let NEAR accounts act as destinations that web apps and users can trust.

At the core is a verification protocol that uses DNS TXT records as a bridge.

The TXT record follows a structured format, for example:

nds=ncaptcha.near:https://ncaptcha.xyz/:8Qe2m1ws9hepfnRypPkgT6gqveCm9BRhrCk46UiTvsPi

This line contains three main parts:

-

The NEAR account (

ncaptcha.near). -

The Web2 URL (

https://ncaptcha.xyz/). -

NEAR transaction hash

Together, they say: “This domain and this NEAR account belong together, and this specific transaction proves it.”

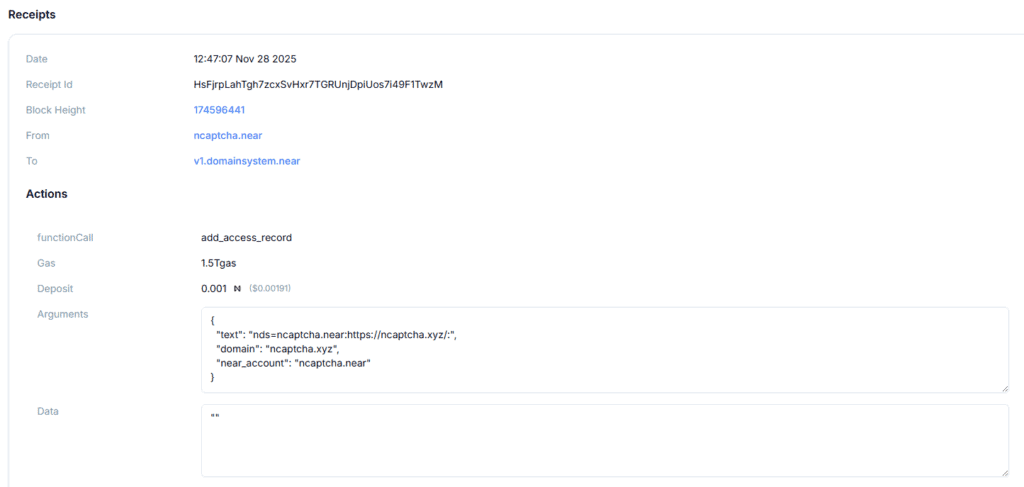

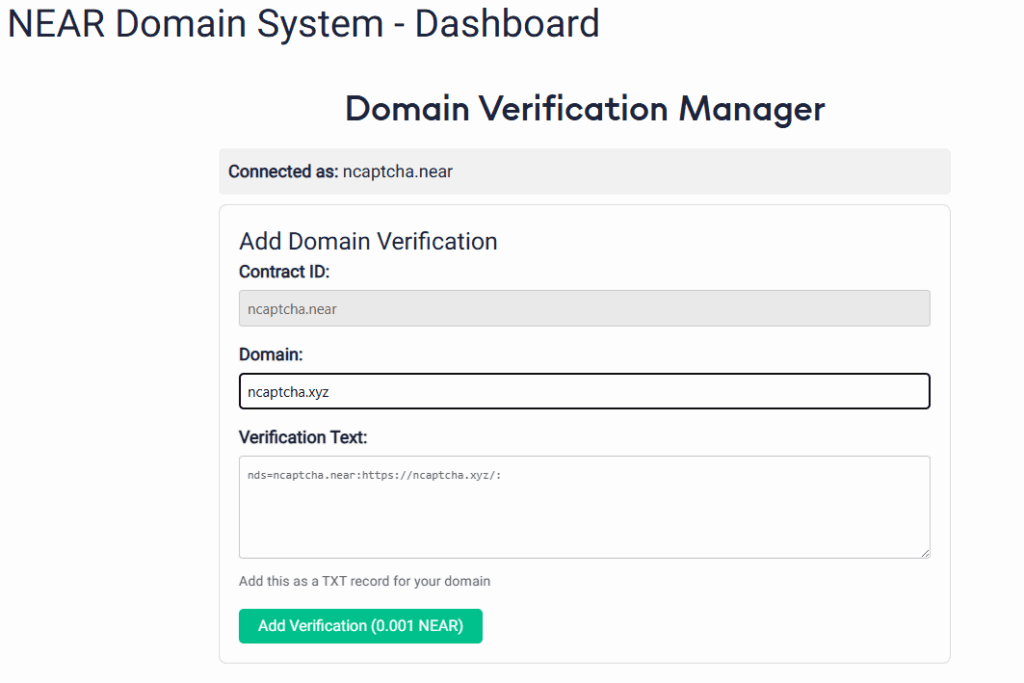

How the NDS Verification Flow Works

Here is a simplified version of the verification flow:

-

Start on NEAR

-

The domain owner signs in as

ncaptcha.nearand calls an NDS contract (for example, via a dApp like “Domain Verification Manager”). -

The contract records the request onchain. Transaction hash must be added as a part of TXT record to bind NEAR with DNS.

-

-

Get the TXT record string

-

The contract returns a string like

nds=ncaptcha.near:https://ncaptcha.xyz/:<transaction_hash>.

-

-

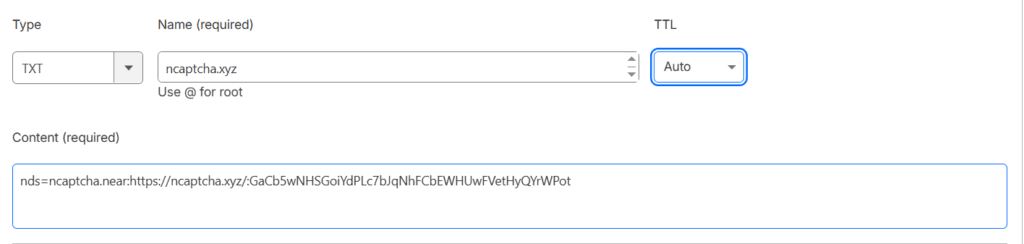

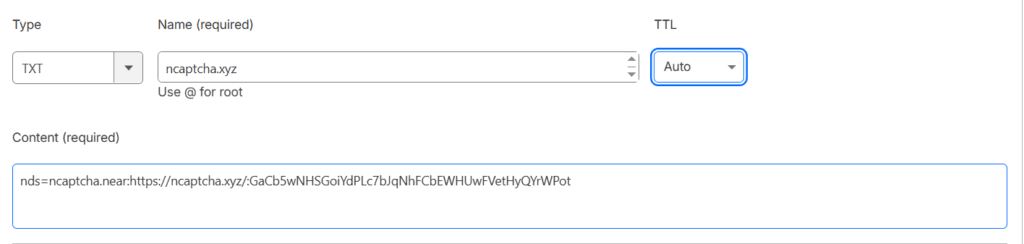

Update DNS

-

The user logs into their DNS provider (GoDaddy, Cloudflare, etc.).

-

They create a TXT record for

ncaptcha.xyzand paste thisnds=string.

-

-

Verification step

-

At NDS Verify the user clicks “Verify”

-

An oracle or backend service looks up the TXT record for

ncaptcha.xyz

Hint: you can use Google service instead: https://dns.google/resolve?name=ncaptcha.xyz&type=TXT -

It checks that the

nds=line exists and that the token matches the on-chain transaction. -

Any app can now query the NDS registry and see that

ncaptcha.near↔ncaptcha.xyzis a valid, public, verifiable pair.

-

This is like a digital handshake between WWW and Web3, using a small TXT record as the bridge.

Why This Bridge Matters

Linking NEAR accounts and WWW domains has clear benefits:

-

Trust: Users can check that a NEAR account really belongs to the same entity behind a familiar website.

-

Simplicity: The same human-readable name can act as a wallet, a website entry point, and an app identity.

-

Compatibility: NDS reuses existing DNS infrastructure instead of trying to replace it.

The Bigger Picture: Towards a Convergent Web

NDS fits into NEAR’s broader vision of chain abstraction.

Projects like NameSky go further by turning NEAR accounts into NFTs, creating a market for names that can also be cryptographically linked to real-world brands (for example, matching nike.near with nike.com).

It’s about proving who’s real in an internet full of AI-generated slop: cloned sites, fake brands, and copy-paste junk that all looks “good enough.”

On top of that, NEAR’s subaccounts (app.brand.near, ai.brand.near, promo1.brand.near) give you a provenance tree. If you trust brand.near, you can also trust the subaccounts it creates. Each app, AI agent, or campaign can live under its parent, with a clear, inspectable trail of “who issued what” baked into the namespace.

The long-term goal is a unified identity layer where one human-readable name can act as your wallet, your website, your login, and your reputation badge across both WWW and Web3.

Takeaway

The NEAR Domain System shows that we do not need to choose between the old web and the new one. By reusing DNS TXT records and making human-readable names a native part of the protocol, NEAR builds a practical bridge between WWW domains and Web3 accounts.

Reflective Questions

-

How would your own experience with Web3 change if you could trust one simple name across websites, wallets, and apps?

-

If you were designing a dApp on NEAR, how might you use NDS verification to signal trust to new users?

-

In your opinion, should future identity systems focus on extending DNS, replacing it, or tightly integrating with it like NDS does?

Updated: December 3, 2025

Top comment

DNSSEC = coordinate DNS provider + registrar + support tickets just to prove DNS integrity. Old school infrastructure problem.NDS = one TXT record + one NEAR tx. The hash IS the proof. Verify on-chain in seconds.Simpler, Web3-native identity linking. 👌

🧑 100% userGreat information, with all the details about the difference with the wallet´s name on the internet

🧑 100% user